Target Audience

AI developers, Product managers

Techniques

Human evaluation, Automated metrics, Task-specific testing, A/B testing

Evaluation Goals

Quality, Safety, Consistency, Performance

Explore essential techniques for evaluating Large Language Model (LLM) responses, crucial for high-quality AI products. Coverage includes human evaluation, automated metrics, task-specific assessments, and A/B testing. The importance of continuous evaluation is emphasized, addressing challenges like subjectivity and bias detection. Best practices include combining multiple techniques, using diverse test sets, and implementing ethical guidelines. The post introduces popular evaluation tools such as Snorkel, Ragas, AWS tools, and DeepEval. Rigorous evaluation plays a critical role in harnessing LLM potential while mitigating risks and building user trust. The need for evolving evaluation standards is highlighted as LLM capabilities advance, stressing transparent reporting and incorporating real-world performance data.

For an AI model to be useful in specific contexts, it often needs access to background knowledge. For example, customer support chatbots need knowledge about the specific business they’re being used for, and legal analyst bots need to know about a vast array of past cases.

Developers typically enhance an AI model’s knowledge using Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). RAG is a method that retrieves relevant information from a knowledge base and appends it to the user’s prompt, significantly enhancing the model’s response. The problem is that traditional RAG solutions remove context when encoding information, which often results in the system failing to retrieve the relevant information from the knowledge base.

In this post, we outline a method that dramatically improves the retrieval step in RAG. The method is called “Contextual Retrieval” and uses two sub-techniques: Contextual Embeddings and Contextual BM25. This method can reduce the number of failed retrievals by 49% and, when combined with reranking, by 67%. These represent significant improvements in retrieval accuracy, which directly translates to better performance in downstream tasks.

You can easily deploy your own Contextual Retrieval solution with Claude with our cookbook.

A note on simply using a longer prompt

Sometimes the simplest solution is the best. If your knowledge base is smaller than 200,000 tokens (about 500 pages of material), you can just include the entire knowledge base in the prompt that you give the model, with no need for RAG or similar methods.

A few weeks ago, we released prompt caching for Claude, which makes this approach significantly faster and more cost-effective. Developers can now cache frequently used prompts between API calls, reducing latency by > 2x and costs by up to 90% (you can see how it works by reading our prompt caching cookbook).

However, as your knowledge base grows, you’ll need a more scalable solution. That’s where Contextual Retrieval comes in.

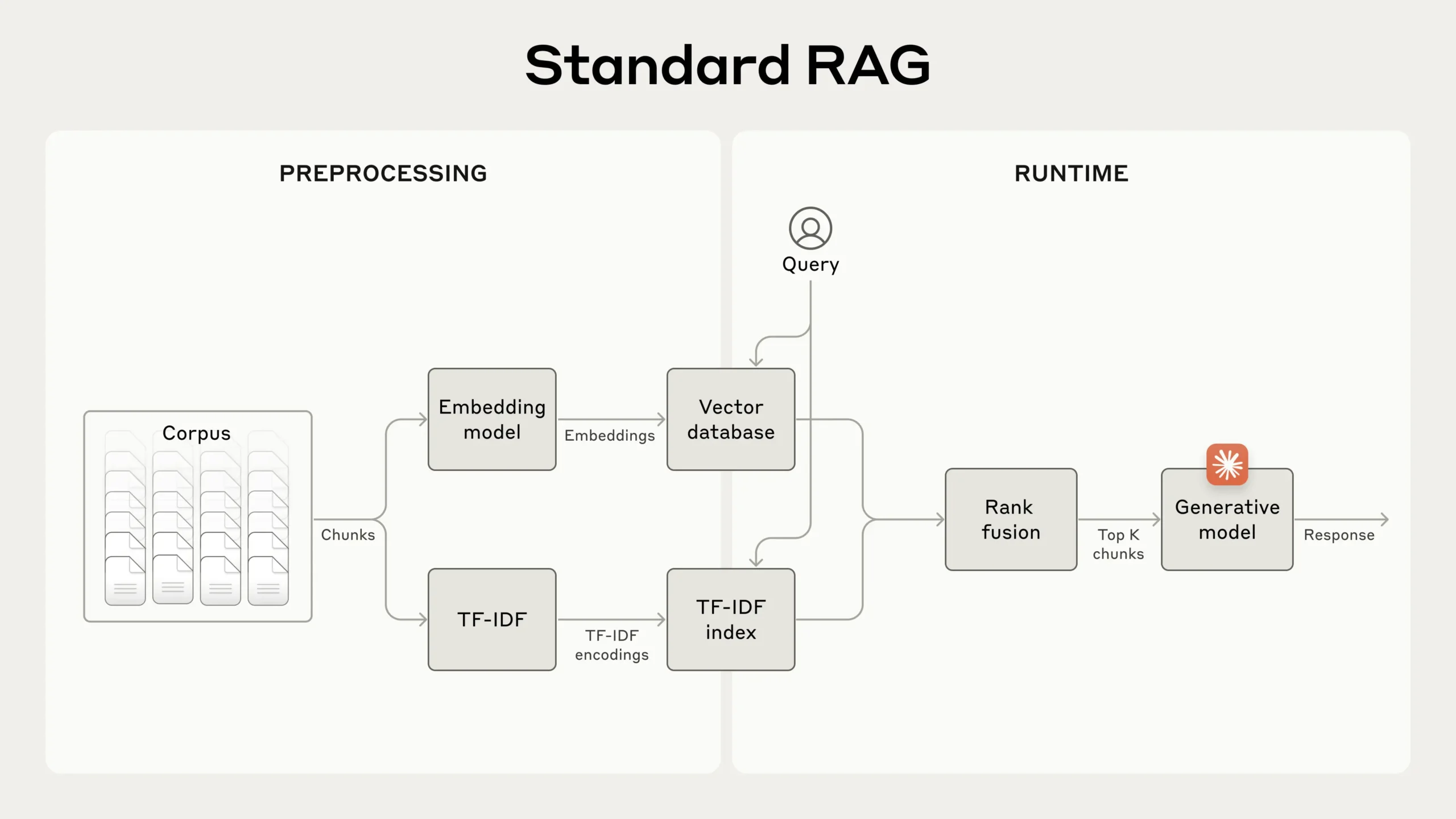

A primer on RAG: scaling to larger knowledge bases

For larger knowledge bases that don’t fit within the context window, RAG is the typical solution. RAG works by preprocessing a knowledge base using the following steps:

- Break down the knowledge base (the “corpus” of documents) into smaller chunks of text, usually no more than a few hundred tokens;

- Use an embedding model to convert these chunks into vector embeddings that encode meaning;

- Store these embeddings in a vector database that allows for searching by semantic similarity.

At runtime, when a user inputs a query to the model, the vector database is used to find the most relevant chunks based on semantic similarity to the query. Then, the most relevant chunks are added to the prompt sent to the generative model.

While embedding models excel at capturing semantic relationships, they can miss crucial exact matches. Fortunately, there’s an older technique that can assist in these situations. BM25 (Best Matching 25) is a ranking function that uses lexical matching to find precise word or phrase matches. It’s particularly effective for queries that include unique identifiers or technical terms.

BM25 works by building upon the TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) concept. TF-IDF measures how important a word is to a document in a collection. BM25 refines this by considering document length and applying a saturation function to term frequency, which helps prevent common words from dominating the results.

Here’s how BM25 can succeed where semantic embeddings fail: Suppose a user queries “Error code TS-999” in a technical support database. An embedding model might find content about error codes in general, but could miss the exact “TS-999” match. BM25 looks for this specific text string to identify the relevant documentation.

RAG solutions can more accurately retrieve the most applicable chunks by combining the embeddings and BM25 techniques using the following steps:

- Break down the knowledge base (the “corpus” of documents) into smaller chunks of text, usually no more than a few hundred tokens;

- Create TF-IDF encodings and semantic embeddings for these chunks;

- Use BM25 to find top chunks based on exact matches;

- Use embeddings to find top chunks based on semantic similarity;

- Combine and deduplicate results from (3) and (4) using rank fusion techniques;

- Add the top-K chunks to the prompt to generate the response.

By leveraging both BM25 and embedding models, traditional RAG systems can provide more comprehensive and accurate results, balancing precise term matching with broader semantic understanding.

This approach allows you to cost-effectively scale to enormous knowledge bases, far beyond what could fit in a single prompt. But these traditional RAG systems have a significant limitation: they often destroy context.

The context conundrum in traditional RAG

In traditional RAG, documents are typically split into smaller chunks for efficient retrieval. While this approach works well for many applications, it can lead to problems when individual chunks lack sufficient context.

For example, imagine you had a collection of financial information (say, U.S. SEC filings) embedded in your knowledge base, and you received the following question: “What was the revenue growth for ACME Corp in Q2 2023?”

A relevant chunk might contain the text: “The company’s revenue grew by 3% over the previous quarter.” However, this chunk on its own doesn’t specify which company it’s referring to or the relevant time period, making it difficult to retrieve the right information or use the information effectively.

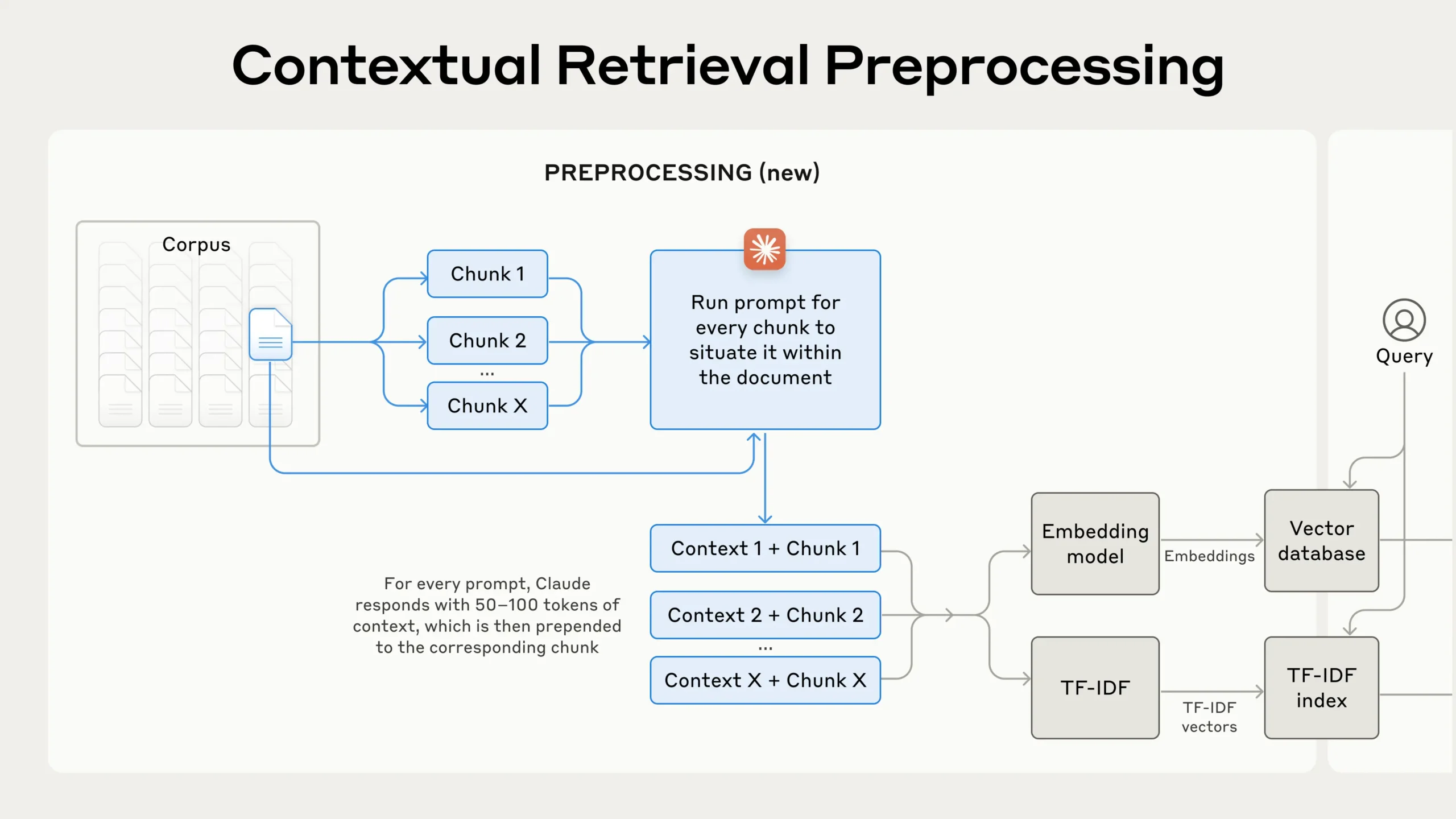

Introducing Contextual Retrieval

Contextual Retrieval solves this problem by prepending chunk-specific explanatory context to each chunk before embedding (“Contextual Embeddings”) and creating the BM25 index (“Contextual BM25”).

Let’s return to our SEC filings collection example. Here’s an example of how a chunk might be transformed:

original_chunk = “The company’s revenue grew by 3% over the previous quarter.”

contextualized_chunk = “This chunk is from an SEC filing on ACME corp’s performance in Q2 2023; the previous quarter’s revenue was $314 million. The company’s revenue grew by 3% over the previous quarter.”

It is worth noting that other approaches to using context to improve retrieval have been proposed in the past. Other proposals include: adding generic document summaries to chunks (we experimented and saw very limited gains), hypothetical document embedding, and summary-based indexing (we evaluated and saw low performance). These methods differ from what is proposed in this post.

import pytest

from your_llm_module import generate_response

def test_prompt_response():

prompt = "What is the capital of France?"

expected_keywords = ["Paris", "city", "France", "capital"]

response = generate_response(prompt)

assert all(keyword.lower() in response.lower() for keyword in expected_keywords), \

f"Response '{response}' does not contain all expected keywords: {expected_keywords}"

assert len(response.split()) >= 10, \

f"Response '{response}' is too short. Expected at least 10 words."

assert not any(bad_word in response.lower() for bad_word in ["inappropriate", "offensive"]), \

f"Response '{response}' contains inappropriate language."

It is worth noting that other approaches to using context to improve retrieval have been proposed in the past. Other proposals include: adding generic document summaries to chunks (we experimented and saw very limited gains), hypothetical document embedding, and summary-based indexing (we evaluated and saw low performance). These methods differ from what is proposed in this post.

Implementing Contextual Retrieval

Of course, it would be far too much work to manually annotate the thousands or even millions of chunks in a knowledge base. To implement Contextual Retrieval, we turn to Claude. We’ve written a prompt that instructs the model to provide concise, chunk-specific context that explains the chunk using the context of the overall document. We used the following Claude 3 Haiku prompt to generate context for each chunk:

<document>

{{WHOLE_DOCUMENT}}

</document>

Here is the chunk we want to situate within the whole document

<chunk>

{{CHUNK_CONTENT}}

</chunk>

Please give a short succinct context to situate this chunk within the overall document for the purposes of improving search retrieval of the chunk. Answer only with the succinct context and nothing else.

The resulting contextual text, usually 50-100 tokens, is prepended to the chunk before embedding it and before creating the BM25 index.

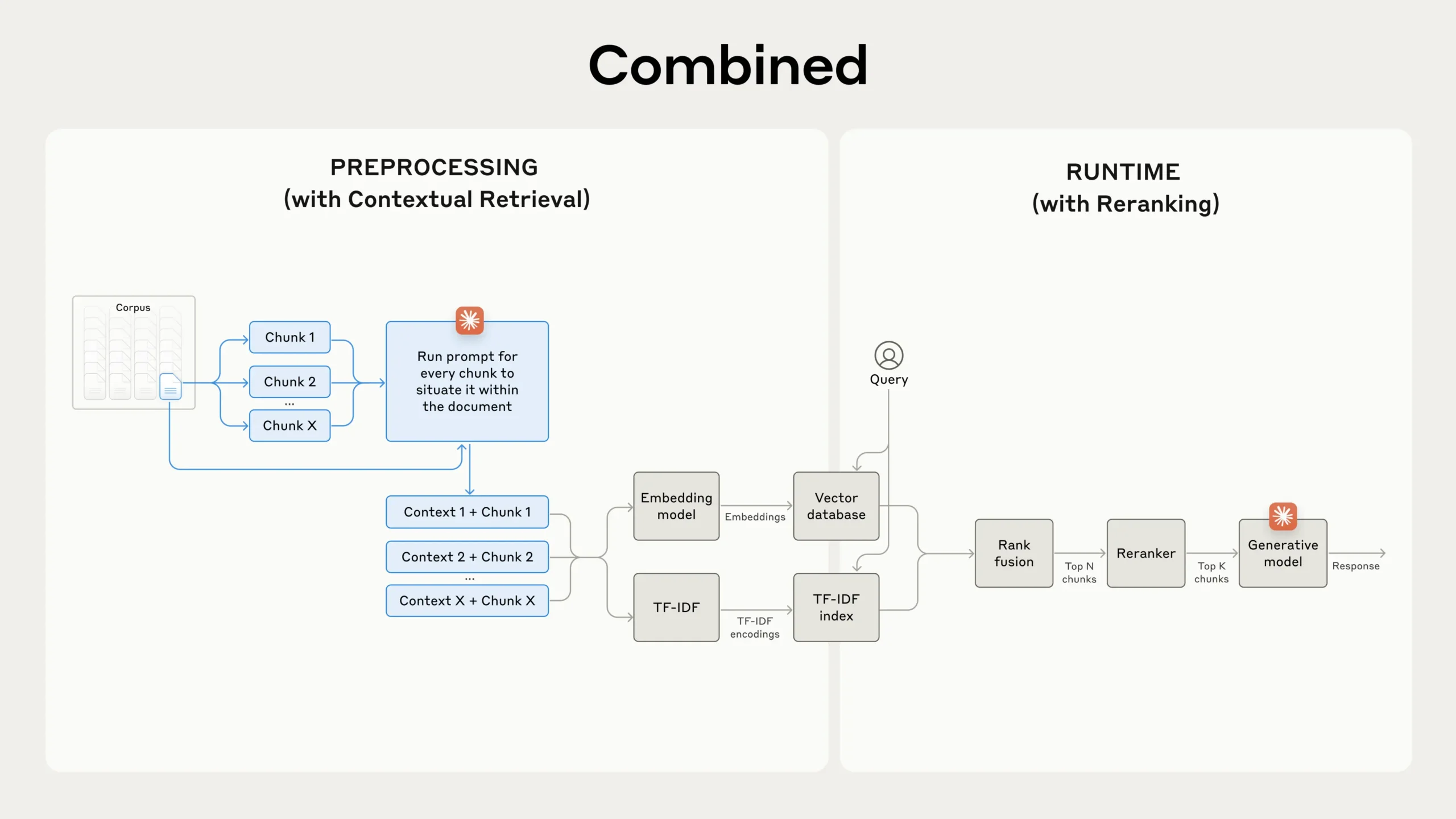

Here’s what the preprocessing flow looks like in practice:

If you’re interested in using Contextual Retrieval, you can get started with our cookbook.

Using Prompt Caching to reduce the costs of Contextual Retrieval

Contextual Retrieval is uniquely possible at low cost with Claude, thanks to the special prompt caching feature we mentioned above. With prompt caching, you don’t need to pass in the reference document for every chunk. You simply load the document into the cache once and then reference the previously cached content. Assuming 800 token chunks, 8k token documents, 50 token context instructions, and 100 tokens of context per chunk, the one-time cost to generate contextualized chunks is $1.02 per million document tokens.

Methodology

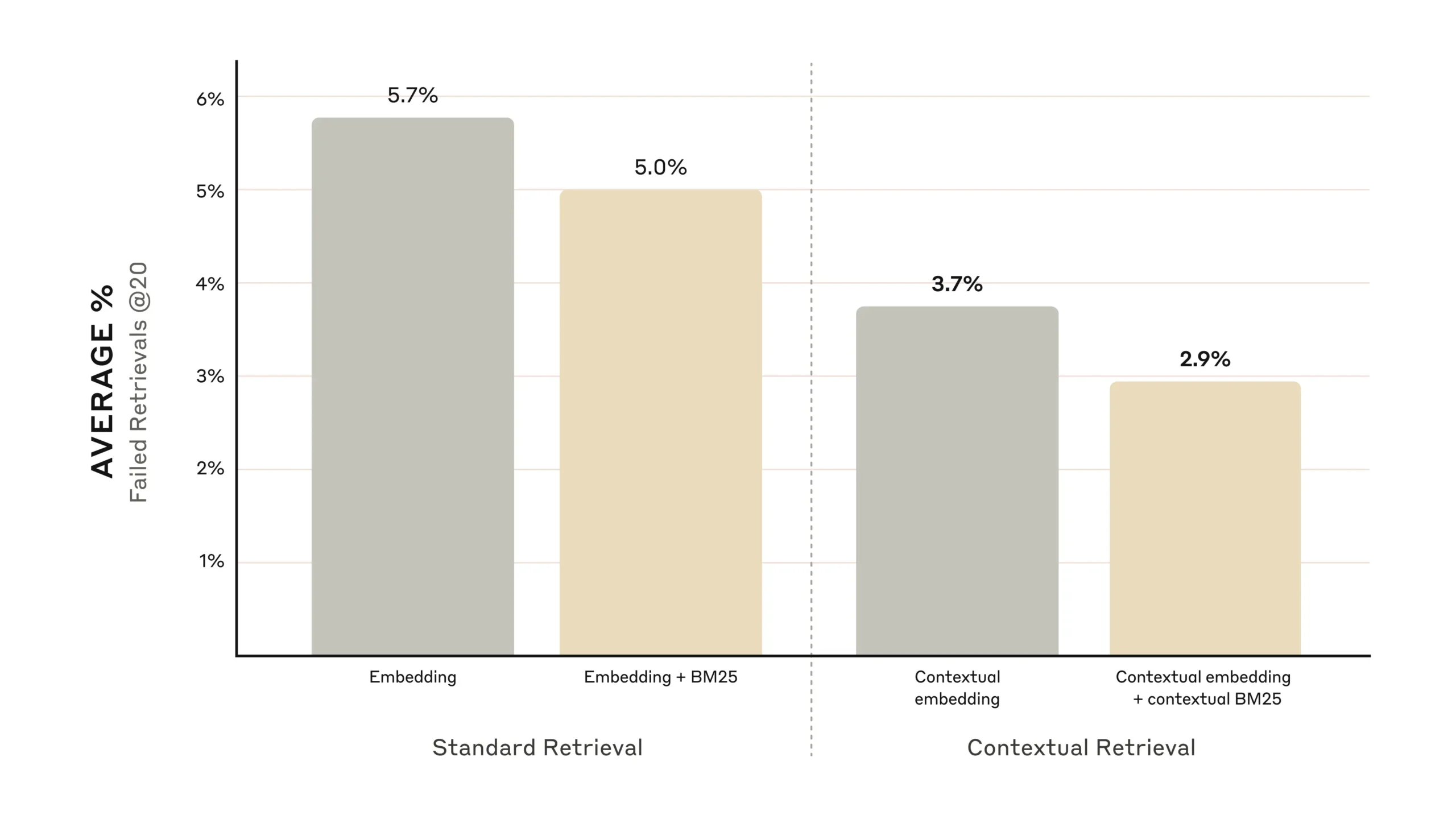

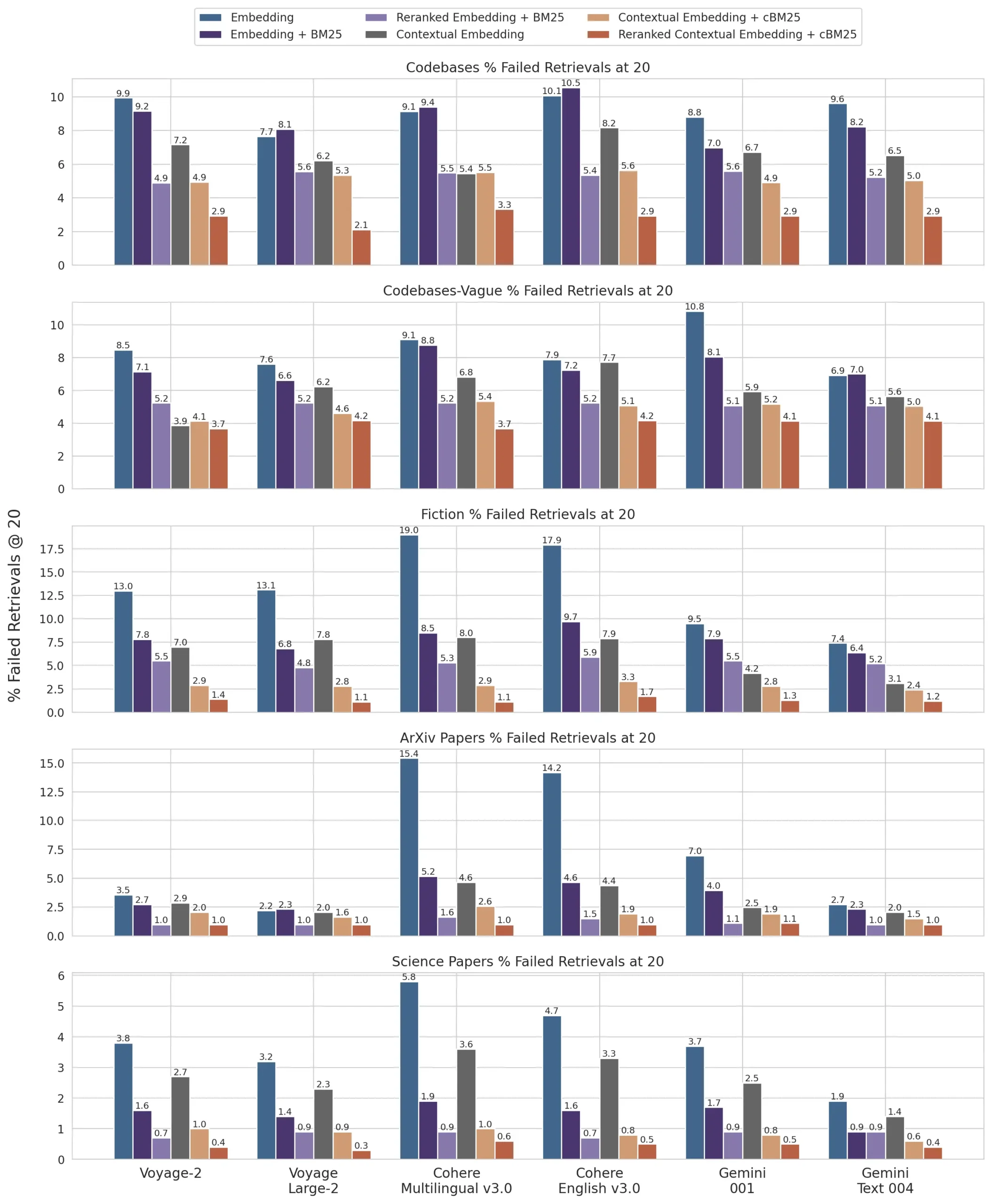

We experimented across various knowledge domains (codebases, fiction, ArXiv papers, Science Papers), embedding models, retrieval strategies, and evaluation metrics. We’ve included a few examples of the questions and answers we used for each domain in Appendix II.

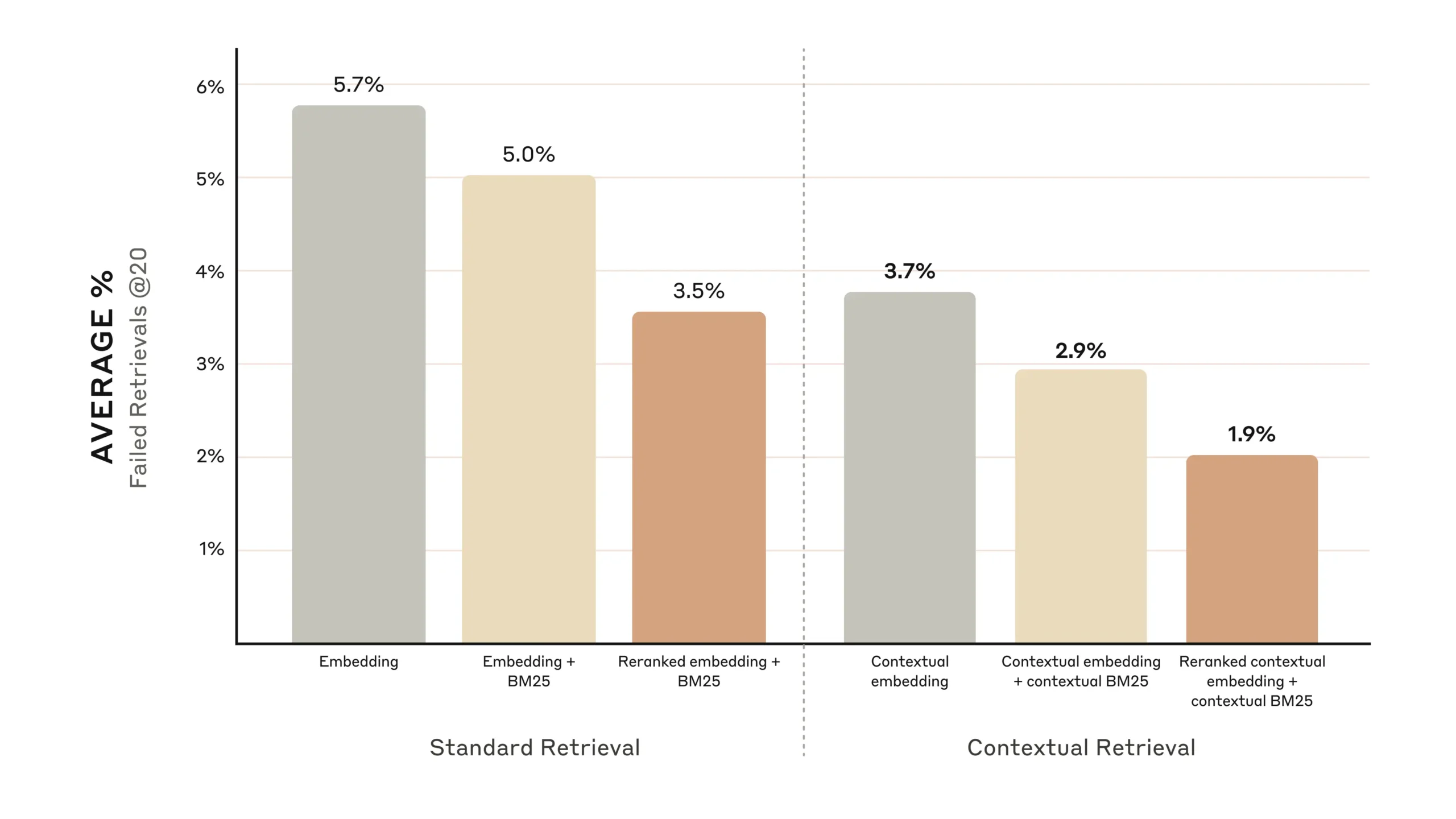

The graphs below show the average performance across all knowledge domains with the top-performing embedding configuration (Gemini Text 004) and retrieving the top-20-chunks. We use 1 minus recall@20 as our evaluation metric, which measures the percentage of relevant documents that fail to be retrieved within the top 20 chunks. You can see the full results in the appendix – contextualizing improves performance in every embedding-source combination we evaluated.

Performance improvements

Our experiments showed that:

- Contextual Embeddings reduced the top-20-chunk retrieval failure rate by 35% (5.7% → 3.7%).

- Combining Contextual Embeddings and Contextual BM25 reduced the top-20-chunk retrieval failure rate by 49% (5.7% → 2.9%).

Implementation considerations

When implementing Contextual Retrieval, there are a few considerations to keep in mind:

- Chunk boundaries: Consider how you split your documents into chunks. The choice of chunk size, chunk boundary, and chunk overlap can affect retrieval performance1.

- Embedding model: Whereas Contextual Retrieval improves performance across all embedding models we tested, some models may benefit more than others. We found Gemini and Voyage embeddings to be particularly effective.

- Custom contextualizer prompts: While the generic prompt we provided works well, you may be able to achieve even better results with prompts tailored to your specific domain or use case (for example, including a glossary of key terms that might only be defined in other documents in the knowledge base).

- Number of chunks: Adding more chunks into the context window increases the chances that you include the relevant information. However, more information can be distracting for models so there’s a limit to this. We tried delivering 5, 10, and 20 chunks, and found using 20 to be the most performant of these options (see appendix for comparisons) but it’s worth experimenting on your use case.

Always run evals: Response generation may be improved by passing it the contextualized chunk and distinguishing between what is context and what is the chunk.

Further boosting performance with Reranking

In a final step, we can combine Contextual Retrieval with another technique to give even more performance improvements. In traditional RAG, the AI system searches its knowledge base to find the potentially relevant information chunks. With large knowledge bases, this initial retrieval often returns a lot of chunks—sometimes hundreds—of varying relevance and importance.

Reranking is a commonly used filtering technique to ensure that only the most relevant chunks are passed to the model. Reranking provides better responses and reduces cost and latency because the model is processing less information. The key steps are:

- Perform initial retrieval to get the top potentially relevant chunks (we used the top 150);

- Pass the top-N chunks, along with the user’s query, through the reranking model;

- Using a reranking model, give each chunk a score based on its relevance and importance to the prompt, then select the top-K chunks (we used the top 20);

- Pass the top-K chunks into the model as context to generate the final result.

Performance improvements

There are several reranking models on the market. We ran our tests with the Cohere reranker. Voyage also offers a reranker, though we did not have time to test it. Our experiments showed that, across various domains, adding a reranking step further optimizes retrieval.

Specifically, we found that Reranked Contextual Embedding and Contextual BM25 reduced the top-20-chunk retrieval failure rate by 67% (5.7% → 1.9%).

Cost and latency considerations

One important consideration with reranking is the impact on latency and cost, especially when reranking a large number of chunks. Because reranking adds an extra step at runtime, it inevitably adds a small amount of latency, even though the reranker scores all the chunks in parallel. There is an inherent trade-off between reranking more chunks for better performance vs. reranking fewer for lower latency and cost. We recommend experimenting with different settings on your specific use case to find the right balance.

Conclusion

We ran a large number of tests, comparing different combinations of all the techniques described above (embedding model, use of BM25, use of contextual2 retrieval, use of a reranker, and total # of top-K results retrieved), all across a variety of different dataset types. Here’s a summary of what we found:

- Embeddings+BM25 is better than embeddings on their own;

- Voyage and Gemini have the best embeddings of the ones we tested;

- Passing the top-20 chunks to the model is more effective than just the top-10 or top-5;

- Adding context to chunks improves retrieval accuracy a lot;

- Reranking is better than no reranking;

- All these benefits stack: to maximize performance improvements, we can combine contextual embeddings (from Voyage or Gemini) with contextual BM25, plus a reranking step, and adding the 20 chunks to the prompt.

We encourage all developers working with knowledge bases to use our cookbook to experiment with these approaches to unlock new levels of performance.

Appendix I

Below is a breakdown3 of results across datasets, embedding providers, use of BM25 in addition to embeddings, use of contextual retrieval, and use of reranking for Retrievals @ 20.

See Appendix II for the breakdowns for Retrievals @ 10 and @ 5 as well as example questions and answers for each dataset.

Footnotes

- For additional reading on chunking strategies, check out this link and this link. ↩︎

- Michelle put this footnote in because she wanted to see what happened with spacing. And what happens if it is a really long footnote. You never know what people can say about a footnote. ↩︎

- Break down and break dance. This is the last footnote. ↩︎

Simulating the bottom of a page without a Footnotes

One important consideration with reranking is the impact on latency and cost, especially when reranking a large number of chunks. Because reranking adds an extra step at runtime, it inevitably adds a small amount of latency, even though the reranker scores all the chunks in parallel. There is an inherent trade-off between reranking more chunks for better performance vs. reranking fewer for lower latency and cost. We recommend experimenting with different settings on your specific use case to find the right balance.

Tables

How this was made: I took a screenshot from Prompt caching with Claude \ Anthropic and asked Claude to write the markdown table. Then I pasted it in the Gutenberg Editor. I create a class for my tables called “table_like_anthropic_mp” and styled it in Elementor > Custom Code. I also created a Gutenburg pattern called “Table Like Anthropic MP“

Example 1: Using My Gutenberg Pattern

| Header 1: My Pattern Table | Header 2 | Header 3 | Header 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| This Pattern uses a CSS Class • I used Elementor’s Custom Code • It’s only to be used for tables | $3 / MTok | • $3.75 / MTok – Cache write • $0.30 / MTok – Cache read | $15 / MTok |

| It follows Anthropic Styling • Borders was the most difficult • Has font size and spacing too | $15 / MTok | • $18.75 / MTok – Cache write • $1.50 / MTok – Cache read | $75 / MTok |

| Use Gutenberg Options too • Fixed width table cells, bold • Header sections, text alignment | $0.25 / MTok | • $0.30 / MTok – Cache write • $0.03 / MTok – Cache read | $1.25 / MTok |

Remove the Section Header.

| This Pattern uses a CSS Class • I used Elementor’s Custom Code • It’s only to be used for tables | $3 / MTok | • $3.75 / MTok – Cache write • $0.30 / MTok – Cache read | $15 / MTok |

| It follows Anthropic Styling • Borders was the most difficult • Has font size and spacing too | $15 / MTok | • $18.75 / MTok – Cache write • $1.50 / MTok – Cache read | $75 / MTok |

| Use Gutenberg Options too • Fixed width table cells, bold • Header sections, text alignment | $0.25 / MTok | • $0.30 / MTok – Cache write • $0.03 / MTok – Cache read | $1.25 / MTok |

Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here. Paragraph is here.

Example 3

You can paste in a markdown table, and then just give it the class “table_like_anthropic_mp“.

| Use case | Latency w/o caching (time to first token) | Latency w/ caching (time to first token) | Cost reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chat with a book (100,000 token cached prompt) [1] | 11.5s | 2.4s (-79%) | -90% |

| Many-shot prompting (10,000 token prompt) [1] | 1.6s | 1.1s (-31%) | -86% |

| Multi-turn conversation (10-turn convo with a long system prompt) [2] | ~10s | ~2.5s (-75%) | -53% |

Sometimes you need a paragraph. Please review the screenshot of this table rendered on a webpage. Your task is to create a markdown version of this table. There are 4 columns and 4 rows. Ensure you bold the appropriate text too as per the screenshot. output as a markdown code block. Ensure VALID markdown syntax. I will paste this into the Gutenberg WordPress editor.

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet • Our most intelligent model to date • 200K context window | Input • $3 / MTok | Prompt caching • $3.75 / MTok – Cache write • $0.30 / MTok – Cache read | Output • $15 / MTok |

| Claude 3 Opus • Powerful model for complex tasks • 200K context window | Input • $15 / MTok | Prompt caching • $18.75 / MTok – Cache write • $1.50 / MTok – Cache read | Output • $75 / MTok |

| Claude 3 Haiku • Fastest, most cost-effective model • 200K context window | Input • $0.25 / MTok | Prompt caching • $0.30 / MTok – Cache write • $0.03 / MTok – Cache read | Output • $1.25 / MTok |

You have included actual ascii bullet points in the table. I thought you would have used markdown syntax. Why have you done this?